Ask anyone who grew up in the west end, and they’ll share a High Park story. They lost a glove by the zoo fence. They saw their first snow on the toboggan hill. They shared a first kiss near the bandshell. The High Park neighbourhood holds both the city’s green heart and its long memory.

But this corner of Toronto keeps evolving. Layers of treaty history, colonial ambition, civic generosity, and neighbourhood momentum shape High Park. A country estate became one of the city’s most dynamic green corridors and residential communities. The park moves with Toronto’s rhythm, sometimes quietly, sometimes through llama sightings.

Land Before the City

Long before John George Howard drew up plans for Colborne Lodge, Indigenous peoples used this land for trails, settlements, and seasonal activity. Archaeological findings place human presence here as early as 7,000 BC. The nearby Humber River functioned as a travel corridor, trade route, and lifeline for the Anishinaabe and other Indigenous communities.

Indian Road, still visible in the surrounding street grid, recalls this deeper history. These lands connected people long before Toronto paved them.

A Gift to the City

In 1836, Howard, an English architect and surveyor, and his wife Jemima bought 165 acres between Lake Ontario and Bloor Street. They named it “High Park” for its elevated views of Humber Bay. Howard designed their home, Colborne Lodge, with restrained Georgian lines, installing innovations like indoor plumbing, a furnace, and a rooftop water collection system. Today, Colborne Lodge operates as a museum and cultural site, where visitors explore 19th-century domestic life, civic history, and the Howards’ public-minded legacy.

In 1873, the Howards donated their land to the City of Toronto, setting a clear condition: preserve its natural state and keep it free for the public. Their vision continues to guide how the city stewards this space.

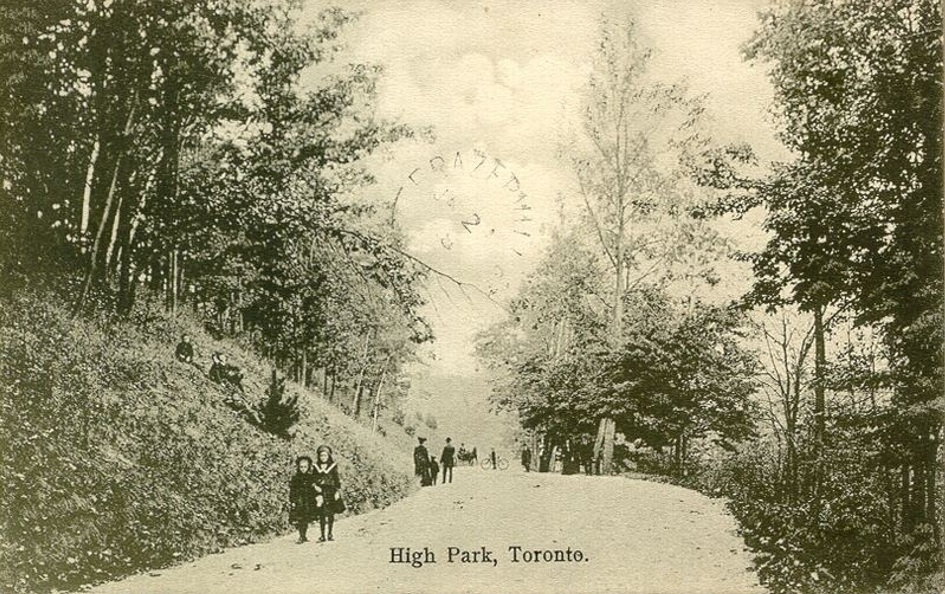

By 1876, the city opened High Park to the public. Workers laid paths, cleared meadows, and created a space for both leisure and shared access.

How the High Park Neighbourhood Took Root

In its early years, High Park stood far from Toronto’s urban core. Farmers maintained the surrounding land through the late 19th century, with only a few homes and dirt roads in sight. Though the park drew visitors, residential growth stalled until transit and roads improved.

In 1915, the city widened Bloor Street, bridging the west end to downtown. Development followed. Builders erected Edwardian and Victorian homes north of the park, many of which still stand shaded by mature trees.

The Zoo and the Pond

In 1893, city officials added a modest zoo to the park. They started with a few deer. Over time, the High Park Zoo grew into a quirky, beloved attraction. Today, it offers free access to bison, capybaras, llamas, peacocks, and other animals. The zoo welcomes more than 500,000 visitors each year with support from the city and community donations.

Grenadier Pond mirrors Toronto’s seasons. Anglers cast lines along its edge while ecologists track its health and bird life. In colder decades, skaters once glided across its frozen surface. Now, visitors use the pond more quietly. Benches face the water. Couples linger.

Mid-Century Acceleration

After World War II, the city expanded quickly. When the Bloor-Danforth subway opened in 1966, High Park became easier to reach. Developers demolished heritage homes on Quebec, Pacific, and High Park Avenues to build concrete towers.

This construction introduced denser, vertical housing. Though some mourned the loss of architectural charm, the new buildings welcomed a wider demographic. In that way, the neighbourhood continued to reflect the Howards’ belief in broad access.

Living in the High Park Neighbourhood Today

Walk north from the park and you’ll move through architectural time. Brick low-rises from the 1930s. Grand Edwardians with detailed lintels. Rounded balconies on mid-century apartments. Clean-lined townhomes tucked behind gardens.

These streets carry a steady rhythm. Dog walkers start the day. Café regulars claim their tables. Cyclists glide toward the lake. Indie shops and bakeries hold their ground on Bloor West. Wellness studios and co-working spaces serve a new generation.

Despite the range in housing, the area feels cohesive. Residents invest in community gardens, ride the bike lanes, and continue to advocate for a free and public zoo. People enter the neighbourhood from different paths, but they treat the space with care, and the space returns the gesture.

High Park as Civic Character

High Park offers both scenery and ritual. Every summer, actors perform Shakespeare near the amphitheatre. Every spring, cherry blossoms call crowds into the open. Toboggans appear when snow falls. Weddings unfold by the greenhouse. Soccer balls get kicked around.

Cherry trees first arrived in 1959, a gift from Tokyo. The Japanese Somei-Yoshino variety became the park’s seasonal hallmark, blooming in pale pink and white. Their beauty lasts only days. The Sakura Project later added 34 more trees to High Park and distributed others across the city, to Exhibition Place, McMaster, York, and the University of Toronto.

Each spring, when the blossoms appear, the park slows. Families, photographers, and picnickers move gently along the paths. The petals tint the air, and the city pauses.

A Living Archive

The High Park neighbourhood integrates the past instead of erasing it. Colborne Lodge continues to offer programming. The trails follow old routes. The zoo fence that once lost a glove still welcomes a new stream of visitors.

Anyone seeking memory, shade, or a story can still find it here. This part of the west end continues to hold space for pause.

No fanfare. Just presence.